After our lost initial trial, we decided to try again, this time with some backup devices that would aid recovery. We still wanted to make sure it was easy to handle the hydrogen, we wanted better documentation of the filling and release process, and we wanted to above all test the app. Because our goals were different and our participation in the contest was no longer an issue, we took some additional liberties. Jesse built a much more attractive enclosure to look like the Apollo re-entry modules.

We added a parachute because the foam was more dense and the payload was heavier.

But the balloon remained the same.

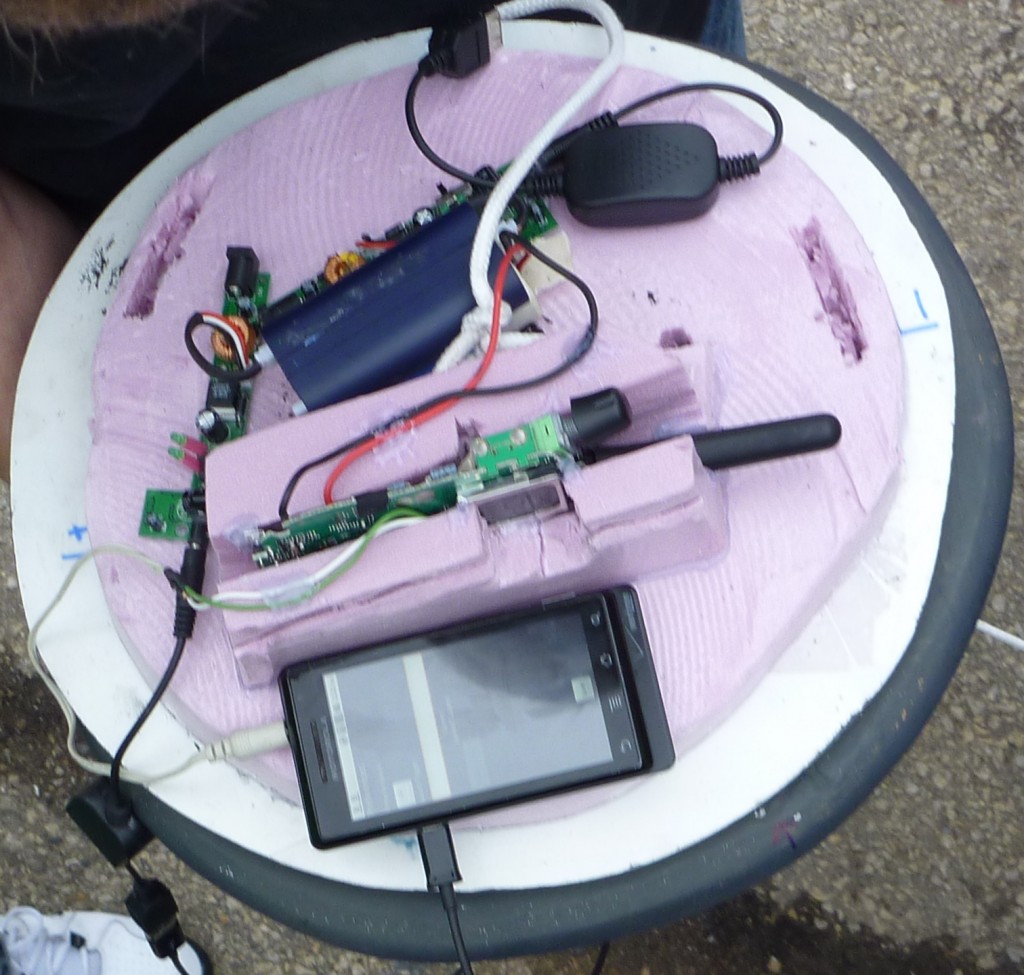

Next we worked on the payload. Because we had no indication of the state of the phone, we wanted a reliable backup phone. Jesse volunteered one of his, and we used the Sprint Family Locator service to track it. The phone itself had no special software running on it; it was just firmly attached to the enclosure. Jesse also had a phone that was set to record video the whole way. It had a window out the side of the enclosure. At the top of the enclosure was another window, this one for the android phone we were testing.

Sadly, the phone caused us a lot of problems. The first phone, also Jesse’s, was an Android version that was too old for the app Issac wrote. It wouldn’t work. Chris volunteered an old G1, but it had an old version of Android as well. We tried to upgrade it to CyanogenMod, but unfortunately bricked the phone in the process, so it was useless. A call for help out to the Sector67 community yielded another potential Android phone. This one was a Verizon phone with a malfunctioning power button. We were able to fix the button (in the sense that we fixed it so we could turn it on, not in the sense that it was working properly as designed), and were back in business. However, since it was a Verizon phone without a plan, we weren’t able to set up a line so that it could text or send data. It would have to operate entirely alone. Well, in a sense. While we were spending time getting the phone to run the software, Issac and Chris were busy rigging up a radio so that it would plug into the headphones of the phone. The radio was set to relay whatever signal went through the headphones, and Issac programmed the app to use the Text To Speech of the phone to relay the coordinates of the device. With a powerful receiver on the ground, we should have been able to hear the phone speaking its location to us long after the balloon had ascended out of cell range.

By 2:30pm, 1/2 hour after we had decided it was too late to launch, let alone leave to go to the launch site, we were finally on our way with all the materials. Well, most of them.

This time our launch location was Mt. Horeb. The wind wasn’t blowing as strong as the first launch day, so it was projected to travel much less. Mt Horeb was a safe distance West that still had us landing between Madison and Lake Michigan. We arrived at our launch site, which was just off the highway, and prepared the tarp and parts.

While the balloon was being inflated, Jesse and Issac were busy getting the payload prepared. This involved making sure the backup phone was on, making sure the video phone was recording, embedding the Android phone into the top of the shuttle (made more difficult by the fact that a critical piece of the styrofoam had accidentally been left behind and the phone hadn’t been inserted with the cables attached and didn’t quite fit), making sure it was running, sealing it all up. In the cold the hot glue was cooling almost instantly, making it all even more difficult.

Finally, everything was ready. We confirmed that we could hear the payload reporting its location over the radio, that everything was connected, and we let it go.

After watching it rise, we packed everything in and waited for it to report its location over the radio. It did not. Shortly after that, I discovered the battery cover for the phone still inside the car. We formed a theory. With nothing else to do, we headed back to Sector67 to remove the tank and wait to hear from the phone. Hopefully after it landed the phone would report its location via the Sprint Family Locator, assuming it landed somewhere with signal.

Fortunately, a little over 2 hours after launch, well into darkness, the phone reported its location, and it was still moving. It had gotten cell signal while still in the air and was on its way down somewhere near a golf course in Jefferson, not too far away. The search team went out and recovered the device.

Fortunately, it was found. Unfortunately, the theory was correct; shortly after letting go the battery to the android phone had fallen out, which is why it was no longer reporting its location via the radio. This also meant that we didn’t have any data recorded about its altitude or coordinates during the trip. No data at all. The video camera had also messed up. Somehow in the hurry of putting it all together, someone had pressed a button on the device to stop it capturing. It’s a good thing we had the backup phone.

It’s amazing we were able to find it in the dark. Once again, the lesson (which we clearly did not learn after the first attempt), was to take things slowly and methodically, and only launch under the best conditions. We were lucky to get this payload back, but it did us no good because we didn’t collect any information at all.